Sometimes you gobble up a book, or sometimes you take your time and savor. This has been a summer of savoring.

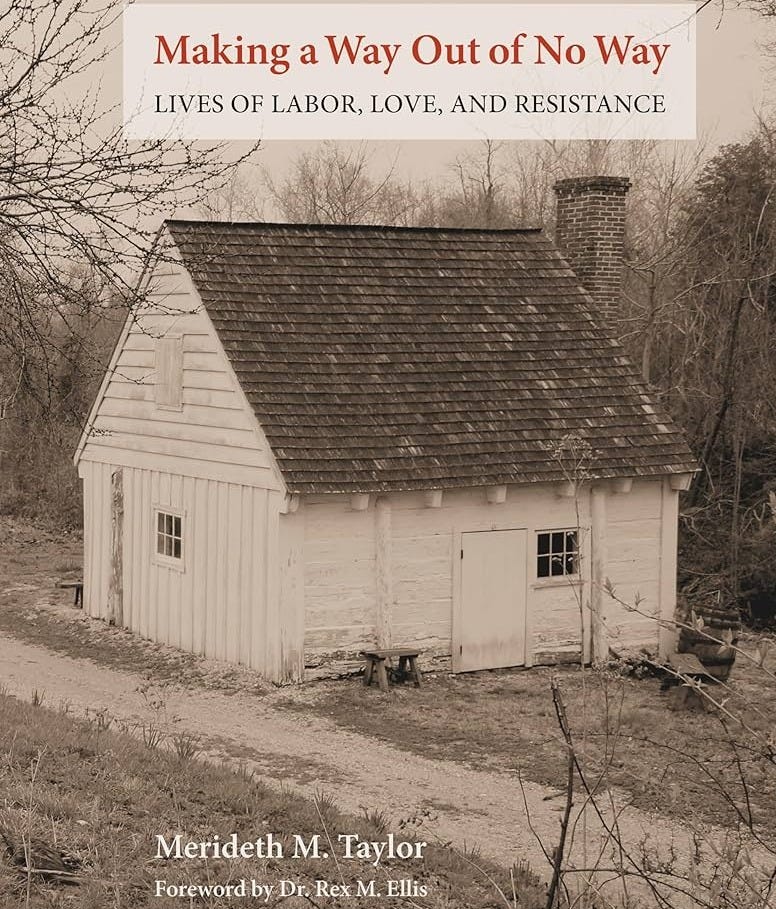

The title, Making a Way Out of No Way, drew me as soon as this book was put in my hands. The phrase is evocative, somewhat sentimental, yet resonant. I heard it occasionally in childhood to describe the everyday courage of African American folks struggling to stay sane and thrive. Making a Way Out of No Way: Lives of Labor, Love, and Resistance by Merideth M. Taylor is a unique book that explores people's bondage on Historic Sotterley Plantation in southern Maryland. Each single-page vignette is told in beautifully descriptive language and examines the inner life of an enslaved person, their work life, their home life, and their relationship to the world around them. Often described by enslavers as farm commodities, the enslaved individual was, in most cases, a skilled worker, an expert in the use of agricultural tools, and an innovator in methods of planting and harvesting crops. Though Merideth Taylor’s text is richly imagined, it is firmly rooted in her years of research on the lives of people enslaved on plantations in Southern Maryland. Taylor envisions these enslaved individuals and describes them with insights and affection. Making a Way Out of No Way is an unconventional novel, a fictional account of specific facts and geography. Historians and historical novelists rely primarily on documents – i.e., diaries, bills of sale, inventories, wills, biographies, autobiographies, photographs, and real estate transactions - to build a picture of the past. Of course, suppressing opportunities for self-expression is critical to maintaining a tractable enslaved population, so literacy was punished severely, and there are few literary accounts of the inner life of the enslaved. The genre of Slave Narrative, accounts of the institution by actual enslaved people, provides much of the mainstream perspective of the enslaved but was often told to intermediaries. These accounts lack frank exploration of the day-to-day life of the enslaved. Making a Way Out of No Way provides this broader view. The book is arranged as short narratives, accompanied by haunting sepia-toned photographs that operate like peeks through a window into daily life and more deeply into the individual’s thoughts. Take a look at the official book trailer: Making a Way Out of No Way

Taylor's unique narrative approach in Making a Way Out of No Way is to use jobs as a way into the interior lives of individuals. She skillfully weaves in photographs of the natural landscape and the tools and machinery of agricultural labor at Sotterley Plantation. The enslaved individuals in the text see and feel the world around them, appreciate its beauty, and understand its many horrors. Each narrative is framed separately from the story preceding or following. The cumulative effect completes a panoramic portrait like a patchwork quilt or a museum installation.

from Making a Way Out of No Way

Upstairs Maid

She had run up and down the steep, narrow servants’ stairs five times already, carrying heavy loads of bedding for the guests who had come to stay with the old mistress for a fortnight. The muscles in her legs were burning, and she was breathing hard. Her toe caught the edge of the top step, and she stumbled, spilling the load of quilts across the floor she’d polished that morning. She scrambled to gather them up, but she was not quick enough, and the old lady’s cane came down with a whack on her back. She wheeled around and grabbed the old lady’s cane, pulling the old lady off balance. And in that instant, she realized the full measure of what she had done. She was in grave danger if the woman told the young master. Meg fell at the woman’s feet, begging forgiveness and promising to do better. “Please have mercy, Missus, on this clumsy girl.” And right then Meg started for a murder so cunning, she’d get clean away with it.

Cutting Barley

As she watched her son swing the heavy scythe smoothly through the barley, Aggie was suddenly struck by how beautiful he was. Fear caught in her throat. He was too pretty for a man! Just coming to manhood, his skin smooth and richly colored, his body well shaped and strong. She’d seen the way Master Robert looked at boys like Dede. And she’d noticed they seemed to disappear from the quarters. Whether they’d been sold off or maybe put to work in the big house, she didn’t know. Maybe they were better off, but she feared a worse fate. But what could she do to protect this beautiful child? What other than pray? Pray that something terrible befall Master before he hurts her boy.

“Being happy is not the only happiness.” True that. I’m going to take that as my new mantra because there are few phrases truer. In the novel, Grace Period, Elisabeth Nonas chronicles the grief of being suddenly bereft of a loved one. People who know me know I know. I don’t need to repeat the details of my tragedy. The death of a life partner – whether parent, child, or spouse – causes the tragically sudden loss of the life and all the plans attached to them. The loved one gone takes with them all the shared life’s goals, big and small. Of course, planning is what we do when we love someone. Children are hardly out of the womb, and we’ve chosen the college they’ll attend or the Olympic gold medals they’ll win. And so, Grace Period takes us down the road of what comes after death. Not the afterlife of heaven or hell, but the daily life that is lived after a loved one dies. Full of knowing observations, it’s not a weepy tome. This is a novel of humor, wry and often chuckle-worthy, also filled with sober insights. Again and again, Grace Period acknowledges that the lives we build together are ephemeral – built on shifting sand. Mostly, what we remember of those intertwined lives are just that: recollections, remembrances of times that have passed. And in the world of grief and its attendant euphemisms, we slog through. Grace Period’s Hannah is a survivor, a woman married to a younger woman preparing for retirement from teaching, with no expectations of living without her spouse. As the elder in the relationship, she imagines herself as “the first to go.” But fate deals her one of those completely unexpected hands, and she picks herself up, navigates the depths of her grief, and keeps on keeping on. Grace Period is a graceful book and a good read.

Because she’s my sister, I have a copy of Cheryl Clarke’s Archive of Style. This recently published book is a collection of Cheryl’s long career in poetry and activism. You can order your copy here: Archive of Style

Clarke’s poetry and essays, centered around the Black, lesbian, feminist experience, have attracted an audience around the world. Her essays, “Lesbianism: an Act of Resistance” and “The Failure to Transform: Homophobia in the Black Community” revolutionized the thinking about lesbians of color and the struggle against homophobia. Her poetry and non-fiction have been reprinted in numerous anthologies and assigned in women and sexuality courses globally. Having published since 1977, Clarke and her work have become a foundational part of LGBTQ literature and activism. Archive of Style is a celebration and homage to one of American literature’s Black Women literary warriors.

from Northwestern University Press

Chery Clarke is with me and Barbara Balliet, a co-founder of the Hobart Festival of Women Writers, an annual celebration of women writers since 2013. Recently, The Hobart Book Village, which sponsors our Festival, was featured on CBS Sunday Morning. Check it out here:

And check out Hobart Book Village on your next upstate road trip.

Thanks for the recommendations. I will add these to my BTR

Thanks Breena for your reading recommendations -- all sounding thought-provoking and digging deep into the psyche and heart. All three books are now on my "to-purchase and read" list.